15.02.–21.06.2020

degree_show – out of KHM

Céline Berger, András Blazsek, Viktor Brim, Anna Ehrenstein, Kerstin Ergenzinger, Denzel Russell, Søren Siebel presents Bas Grossfeldt

Céline Berger, András Blazsek, Viktor Brim, Anna Ehrenstein, Kerstin Ergenzinger, Denzel Russell, Søren Siebel presents Bas Grossfeldt

In their works, the artists in degree_show – out of KHM react to social and natural developments of our time. Their work begins with observation, research, personal cultural backgrounds, and the use of a wide variety of media, with a focus on topics including natural and human resources, tradition and its reinterpretation, exploitation, and capitalism.

All the films, pictures, performances, and installations featured in the exhibition deal with the relationship between people and places. They tell stories of workers, prisoners, artists, and different social groups. They deal with the destruction of nature and its influence on human life. The exhibition offers information, questions everyday patterns, and makes room for a longing for the essential: at the end of the space, visitors can let sound and movement, rain and wind carry them away and reflect on what they have seen and heard.

The show brings together time- and media-based works by students and graduates of the Academy of Media Arts Cologne.

The exhibition is curated by Gertrud Peters and Mischa Kuball.

Transpositions: Artistic Research and Embodied Experience

Lilian Haberer

“Visual art as knowledge production is about engaging with ‘difference and the unknown’ in both ‘artistic’ and ‘social-political’ terms.”

Sarat Maharaj

What is artistic research? A searching movement, entering into an as yet unknown field of images, thoughts, and knowledge that is processed and reflected on with artistic means, research, archival and source materials, conversations, studies, etcetera. Anke Haarmann points out that in artistic research a shift to doing and making takes place, “from poesis to practice” and to “art as knowledge production.”[1]. he art theorist and curator Sarat Maharaj describes this creation of knowledge in the above quotation as being open to the unknown, things that differ and deviate, not only in an artistic but also in a political sense. In his engagement with artistic, researching practices, he also emphasizes that thinking with and the creation of art can be understood as a form of experimentation and experience parallel to other knowledge systems and thus also allows a variety of practices. The outcome of this research and the chosen form are thus uncertain.[2]. This openness which characterizes the artworks is both a quality and a challenge for viewing them, since with the different levels of media, diverse approaches to this form of knowledge and research are also conveyed.

The exhibition curated by Gertrud Peters and Mischa Kuball with the pragmatic title degree_show: out of KHM brings together seven artists who studied at the Academy of Media Arts or are still active there. At second glance, in spite of the diversity of the approaches, their interest in backgrounds, causes, and correlations and their methods of artistic research are the connecting element as well as the searching movements associated with them. The concise accompanying text on the exhibition written by Gertrud Peters and Céline Offermans deals with connecting topics such as “the relationship between people and places” and the discussion of social and cultural issues in post-industrial times, in which dealing with nature, work, and the existing raw materials and resources has become product-oriented and their structures are subject to perceptible transformations to which the artists respond with their own media reflections.[3] In addition to these resonances of the topics, the way the artists deal with research and background material also seems to be crucial, as central elements of the artistic video, sound, architectural, and sculptural installations. Their reflections on these traces and artistic preparatory work, which are then echoed in the media-aesthetic works, can be described as “transpositions.”

Within artistic research, the concept of transposition involves a transfer between the score and the performance, but above all a change of perspective, which also concerns the reflection of research material due to this shift in position.[4] The concept was developed by the feminist philosopher Rosi Braidotti, from her book Transpositions: On Nomadic Ethics,[5] which here, applied to artistic research and the works that deal with it, opens up an other, differing space (in the sense of Foucault). Transposing within music, linguistics, medicine and genetics is a common procedure that means shifting keys or exchanging words, organs, or genes. Braidotti describes transpositions as a shift in perception, for example of a multilayered nomadic subject. This results in a ‘transversal’ research practice in our view of things and thus a transfer. Braidotti describes this practice as a “weaving together different strands,” which, in its diversity and multiplicity, creates an “in-between space’” in which both discursive and material-related searching movements arise.[6] The process of artistic research as a transposition is therefore understood as a movement that also refines and shifts our perception of the aesthetic, social, political, and cultural connections. This contribution thus follows the spatial and research movement of all artists.

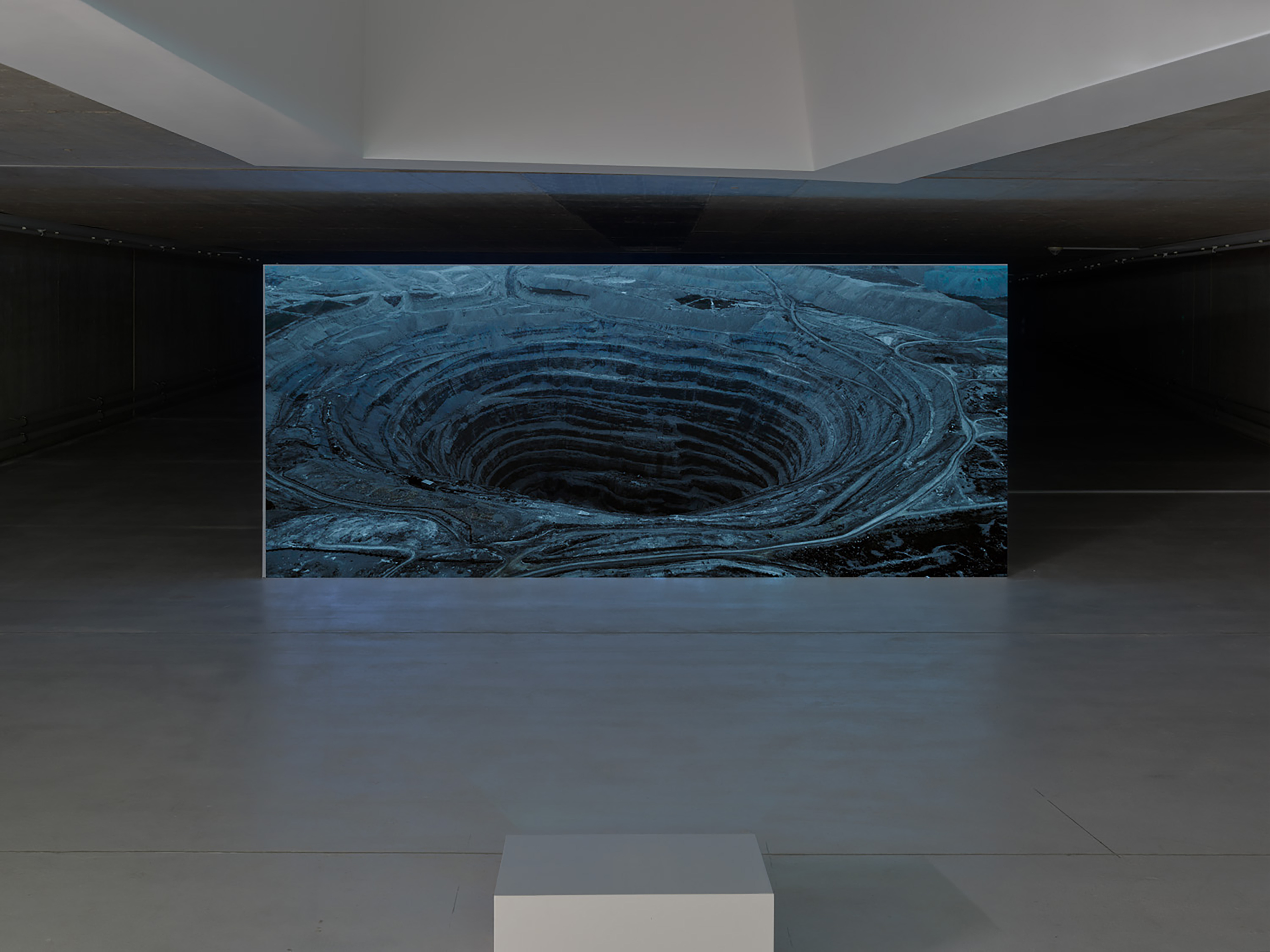

Descending into the exhibition at KIT and traversing the long, sloping space with its striking, elliptical concrete architecture demands an active perception of time. This is apparent at the beginning of the exhibition with the almost 20-minute 4K video Dark Matter and the artist’s book Imperial Objects presented on a display (both 2020) by Viktor Brim. On a free-standing projection screen in Cinemascope format, a foggy, post-apocalyptic landscape with a continuous drone sound gradually becomes visible, and the camera searches for traces of the machines and systems of precarious wage labor in a diamond and gold mine in Yakutia, as if pulled in by the crater. As the title succintly suggests and the artist’s book illuminates in texts with background information, materials such as newspaper articles, postcards, and pictures of the area, the work in the Mir diamond mine around the city of Mirny is also a dark, dangerous, and secret matter. This place is protected by the locally important company Alrosa, as well as by the regional government and Moscow. Some of the mining took place with an atomic bomb test in Yakutia by the Russian government in 1993. Radioactive material as well as traces of the heavy metal industry and rocket parts have thus made the area a toxic landscape. The artist’s book summarizes the topography, history, present condition, and stories related to the mine in several chapters with contrasting colors and offers information about cycles of work and power as well as the environment. Local reports of explosions, toxins, dying animals, damaged nature, and supernatural phenomena, of a “higher authority,” thus form a polyphonic and lively narrative. During his stay in Mirny over the course of several months, Viktor Brim collected material about the mining town and life there, also concentrating on discussions with a worker and on internet forums dealing with secret information about the experiments that took place there. The camera’s slow scanning of this barren, mysteriously dark landscape at the Mir mine, which only shows the machines working on the edges of the crater, makes the destruction and danger to the environment barely palpable. The artist’s book, on the other hand, reveals the traces and experiences of the local people; it gives the film images depth in their own way through the narrative strands of the material.

Following the entrance area, in a narrow passageway that later widens, the black-and-white, almost eleven-minute HD video work Rare Birds in These Lands (2013) by Céline Berger is shown on a monitor with wireless headphones. The open rooms with high ceilings of the Goethe-Institut in Amsterdam are prepared by an actor in business attire for a risk analysis workshop on the opportunities and risks of an artistic intervention in a business context. The participants—artists, businesspeople, and a curator—are to arrive soon, but the video shows the preparations, the empty rooms afterward, and in one moment the closed door during the event. The voiceover summarizes the change of perspective of the participants in two different voices: an artist persona (“he”) and the company (“they”) during the event that has already taken place. In the spoken text, the artist’s side considers his own role, building trust, and the expectations of the businesspeople. The company’s side hope to get help with soft skills communication and trust and expects that the problems and constellations become visible instead of measurable.

The video work was created as part of a studio grant that the artist received at the Rijksakademie and deals with the function of social capital in work contexts. To what extent can artistic work bring about change as an intervention and interaction with employees at the company? During her research, Céline Berger reflects on a precarious moment in the field of art through austerity measures in Dutch institutions, which also raises the question of the role of the artist for society with further education and optimization programs such as TAFT (Training Artists for Innovation) and Geen-Kunst, a management consultancy between art and businesses offering coaching and seminars. In the workshop Berger uses an engineering method that she learned during her first university degree, but afterwards this practice becomes an analysis tool for the group’s failure. For her approach, she dealt with the Artist Placement Group, a British artist collective that has been questioning work structures and analyzing social and economic questions since the 1960s. Instead of distilling the dialogues from the risk analysis itself, she chose informal conversations between the participants, which offer reasons for their failure, in order to generate a counter-narrative to the often repeated success stories with the voiceover and a final brainstorming picture. The camera consciously remains outside of the event itself. It thus circles around the absent, inaccessible session for the viewers and follows the actor behind the scenes. Instead of the polished “risk matrix,” it is expectations, assumptions, comments, and impressions that permeate the setting in a variety of ways. Both video works by Brim and Berger allow viewers to immerse themselves in their surroundings in a different way, with sound and voiceover, but also through varied points of view: sitting directly in front of the screens, standing, or in motion.

The suite of open rooms tapers from one end to the other: starting with the horizontal narrowing through the stairwell, the tunnel widens and converges on the vertical axis. The sculptures Speakers (2020) by András Blazsek are installed in the transition area from the narrow corridor to the wide room with a high ceiling: four rectangular cubes placed overhead, made of MDF panels and melted flat glass with a white 3D-printed funnel element for the membrane evoke loudspeakers placed opposite to each other or slightly offset. On the rear wall of the staircase, with Superposition (2020) made of wood, plaster, and styrofoam, the wall was transformed into a relief of the profile of two superimposed sine waves, since these sound waves are fundamental to hearing. The artist appropriated the central form of devices and instruments for sound amplification, such as loudspeakers, since they represent figures of thought and metaphors for the various, also modulated and manipulated tones and their listening experiences; sound is present here as an idea and imagination, and since there is no real noise here, visitors are challenged to actively listen to the space. For Blazsek, the four forms of listening in the acousmatic field are a central element of his engagement with sound and acoustic equipment inspired by the composer and acoustician Pierre Schaeffer, who theorized musique concrète in 1948 and was pioneering with his publications on music and acousmatics. In contrast to the four modes of hearing, in which the sound source is visible, Schaeffer sees the acousmatic field as an area in which any visual, measurable, or tangible source cannot be seen, whether in a live situation or through loudspeakers. In András Blazsek’s work, Schaeffer’s four modalities—pure hearing, which often happens without preparation; the hearing of different sound effects without seeing how and where they are generated; as well as modifications in listening and in generating the signal[7] – become three forms on which he reflects in his sculptures: pure hearing with the sine wave wall, various sound effects with his speaker sculptures, as well as in the processed and modified signal he sees a parallel to the baskets in his artificial and digitally modified 3D print.

The appropriation and transfer from the area of sound into the visual in Blazsek’s installation is echoed in the field of culture in the next work by Anna Ehrenstein: in the front part of the wide and high suite of rooms directly after Blazsek’s sculptures, with A Lotus Is a Lotus she installed handmade lenticular prints on Dibond and sublimation prints on mesh flag fabric (Capitalocene Safari Fiber I+II, all 2019) on both side walls. She also placed a monitor with a nearly ten-minute found-footage video work on a rod with glass pebbles in the middle of the room. Ehrenstein works with the appropriation of cultural artifacts and the question of originality or counterfeits in the globalized circulation of goods, in which things only serve as codes or tourist souvenirs. While two video chat windows, icons, as well as scratch, image, and sound effects overlap with English texts on the screen, imitating Arabic, Oriental, or Asian characters in their appearance, the prints show a shifting of the intersecting objects, images, and fabrics. In the video, the artist chats with a shopping and tour guide who advises customers from all different continents in China on their purchases, but also discusses their idiosyncrasies and interest in brand-name or counterfeit products. The texts running across the screen deal with projections on cultures, aspects regarding globalization, and the question of how people are evaluated or judged because of the products they use. They deal with the longing for authentic objects, such as oriental carpets, and reflect cultural-studies and post-colonial theories by Arjun Appadurai, Ann Anline Chen, and Fang Yang, among others. In preparing for her project, Anna Ehrenstein dealt with extensive literature on material culture and decolonial developments, especially fabrics and textiles, their exoticizations, their politics, and the form of their presentation in museums. Visual research in markets and interviews with guides from the tourism industry were as important for the artist, as was her research in virtual forums, on various travel platforms, and in dealing with 3D renderings of objects. Both the wall sculptures and the prints on fabric and Dibond encourage visitors to move back and forth, to walk around the works, and to take different perspectives.

This aspect of movement intensifies in the back part of the space with a walk-in fabric architecture, present techno sound patterns, and a work of choreography by Søren Siebel feat. Bas Grossfeldt (the latter is the artist’s musical alter ego). The choreographic acoustic part was only shown at the opening. In Die Architektur des Unbewussten (2020), three long, horizontal triangular shapes made of black, translucent fabric, which are staggered in a row from the sides of the walls, pointing toward the center, create various narrow zones within the space. At the opening, they were used in a live event by the seven performers Brigitte Huezo, Christoph Spelt, Demetris Vasilakis, Helen Franka Burghardt, Isaac Espinoza Hdrobo, Jimin Seo, and Kilian Löderbusch with a score of angular, object-like body movements, almost as appropriations of things in space, parallel to the sound level in resonance with the room. The choreography was developed by them together with Søren Siebel as a vocabulary that has a certain repetitive pattern parallel to the sound and transforms or deconstructs seemingly simple elements such as breathing and walking. In the absence of the movements, as visitors once again walk through this filigree architecture also protecting from view, a panel is placed in each spatial compartment with the description of various bodily movements, which can also include a static position instead of a gesture. As with Blazsek’s Speakers, they also stimulate the imagination. In his artist’s book of the same name, Siebel examined not only drawings of the choreographic movements, abstract scores, and studies of the space, but also the movements of the bodies therein, as well as the ‘relationships between gazes’ and the transparencies of the fabric architecture. The constellation between the three areas of “space,” “body,” and “sound” are essentially linked to concepts that are relevant to him—for example, “atmosphere,” “direction,” “invisible,” “blurring,” “object” for space; “relation,” “limit,” “sequence,” for sound; and “nuance,” “ecstacy,” “intuition” for sound. The word “distortion” and the element of excess are also central themes. This also means overcoming structures and systems, as well as the possibility of creating a common element out of the three structures of space, body, and sound, which are connected, only when their own laws are exceeded—or, as Søren Siebel concludes: to create a derivation of “unconscious self-collective.” By reliving the fabric architecture, the performers and their movements are present in a mental and tactile way in their angular and object-like nature. But they also make the loop of their sequences tangible, which draws viewers into their trance of movement. These correspond to the rhythm patterns of the opening performance, as well, which resonate in Kerstin Ergenzinger’s installation at the end of the exhibition.

Once again, the width of the space becomes visible with an elliptically tapering wall and offers a view of the tall, white cube of the second stairwell. Denzel Russell installed two LED screens on the front and side wall, which he programmed himself on a Raspberry Pi in his 31-minute found-footage work Carceral Companies (2020). Viewing the work demands a certain distance and a wandering movement in front of the screens with burling made of transparent plastic, so that the looped commercials for various American companies can unfold in their model-like manner to a neat and tidy world bathed in warm colors. At times they also show style-forming advertistments for Pepsi with icons such as Kanye West and Beyoncé. All companies benefit directly or indirectly from the increasingly privatized and profitable prison industry, the so-called prison-industrial complex (PIC). In addition to the well-known major companies GEO Group and CoreCivic, which offer incarceration and resocialization services, banks, airlines as well as health care, telecommunications, packaging, vending machine, surveillance system, and technology companies are involved, including J.P. Morgan, Blackrock, ATI, SunTrust, American Airlines, HP Inc., Dell, E&T Plastics, PepperBall, ALPA, IBM, and Tyson. A further 3,000 companies earn significant revenues from the dramatically increasing number of people in prison, which, due to the turbo-capitalist logic of exploitation, primarily affects people living in precarious situations, such as socially and politically disadvantaged people, African Americans, people of color, migrants, and refugees. Russel researched all companies involved in the PIC and created a dossier on a USB flash drive that grew by the day for his project to document the companies involved and those that profit from private prisons. At the same time, the artist compiled the companies’ advertising videos on online platforms such as YouTube, the Internet Archive, and others as a kind of video playlist, in order to examine the visual rhetoric and advertising aesthetics with which they attempt to convince people, focusing on the marketing side of these companies. In addition to his research, he follows Worth Rises, an NGO that is deeply involved in dissolving the prison industrial complex and its profits, and supporting the people it exploits. Russell also finds insight in videos with the singer Beyoncé, who is a role model as a pop idol but also acts as an independent voice for the self-confidence and rights of Black People. With Pepsi commercials, however, she may be inadvertently supporting this supplier of the vending machine industry and the PIC. For Denzel Russell, these advertising sequences are meant to question the function of role models and generate awareness of these sometimes invisible connections, in which every consumer can make a difference by changing their own behavior. The found footage elements of A Lotus Is a Lotus and Carceral Companies present specific aesthetics of online communication and the world of advertising, thus sharpening our perception of the manipulative power of visual cultures and their societies, dependencies, and entanglements.

Meanwhile, visitors open their ears in the last, vertically converging, high and narrow part of KIT to experience a sonic architecture in hearing and listening again, complementary to Siebel’s architecture of movement. With Pluvial (2018), Kerstin Ergenzinger built and programmed a fragile sound installation between a cloud floating in the room, a sculpture, an instrument, and an experimental setting. It consists of five clouds hanging from the ceiling with a total of 80 movable aluminum tubes of different lengths, covered with silicone membranes, with small swinging brass basins above them, which are connected with Nitinol wires. These wires are made of an alloy with a shape memory effect and react to heat, acting almost as instrument strings. With the String-Drum principle, the kinetic Nitinol wires and resonance tubes are vibrated by impulses. At certain intervals, sounds of rain with swelling rhythms and in different intensities spread in the room, reminiscent of white noise. For the artist, the spatial environment is part of the installation, and how locally created noises and sounds spread, and to what extent space can also be an instrument are central questions for her. Ergenzinger had previously experimented with Nitinol wire in Studien zur Sehnsucht and with the String-Drum principle in The Cosmic and the Affective, which was shown in a public place, but in these works she created permanent soundscapes. In Pluvial, by contrast, the rain sounds unfold in space and time in random intervals, their voltage pulses are modulated by the varying intensity of precipitation measurements, from barely audible to expansive rhythms. Similar to András Blazsek’s evocation of hearing, these require active listening and spending time with the work. Between 2016 and 2018, Kerstin Ergenzinger received a grant at the Berlin Centre for Advanced Studies in Arts and Sciences at the Berlin University of the Arts and the Einstein Foundation, where she conducted research along with dancers, artists, and scholars, including the media theorist Eleni Ikoniadou. They investigated theories of rhythm, time, and space, as well as micro-political practices and macro-political questions beyond the media and disciplines. This led to the joint publication What if it won’t stop here? (Archive Books). The interdisciplinary investigation of microstructures between the senses and media of experience is therefore a key concern for Kerstin Ergenzinger. As visitors lie on beanbags, gazing at the sound clouds, the sometimes almost inaudible and then perceptible and powerful sonic forms and rhythms become part of an immaterial but sonic, tactile, and intensely palpable landscape. The exhibition thus reconnects to its beginning with a camera that scans the texture of the inhospitable landscape in Dark Matter.

The result is a constantly changing impression of space, especially due to the featured audiovisual, artistic works and the active exchange with them in contemplation, walking around, and meandering to a multilayered, embodied experience of time. Thus, this extra space created alongside a tunnel used by cars, which bears speed as well as standstill as possible forms of movement, becomes a further and connecting actor in the exhibition. This is true in general of the unique setting of KIT, but it is only the specific and different forms of artistically dealing with this dominant spatial foil which creates different voices and perspectives as well as connections via themes and questions, and challenges our tactile and synesthetic experience, especially in this group exhibition.

The principle of transpositions as a connecting element of these different approaches, which are connected in their research practice and searching movement, becomes not only a synesthetic and tactile media experience when walking and wandering through this series of spaces. Rather, in dealing with social issues as well as the structures, spaces, and ways of thinking associated with them, the artworks reveal a variety and multiplicity that sensitizes one’s own perception in the processing and compilation of the material they use and creates an opening, spaces in between experience and reflection.

- Anke Haarmann, “Verschiebungen im Feld der Kunst,” in: Einundreissig, Ins Offene: Gegenwart: Ästhetik: Theorie, 18/19 (2012), p. 77–82, here p. 77.

- Sarat Maharaj, “Unfinishable Sketch of ‘An Unknown Object in 4 D’: Scenes of Artistic Research,” in: Annette Balkema/Henk Slager (eds.), Artistic Research, New York, 2004, p. 39–58, here p. 39, 45.

- Cf. Céline Offermans/Gertrud Peters, degree_show – out of KHM, KIT Düsseldorf, accompanying text for the exhibition, 2020, p. 1–4, here p. 1.

- This term is the subject of a publication by the Orpheus Institute, a place of artistic research for contemporary music. See Michael Schwab, “Introduction,” in: ibid. (ed.), Transpositions: Aesthetico-epistemic Operators in Artistic Research, Ghent, 2018, p. 7–21, here p. 7–9.Operators in Artistic Research, Ghent 2018, S. 7–21, hier S. 7–9.

- Cf. Rosi Braidotti, Transpositions: On Nomadic Ethics, Cambridge, 2006.

- Ibid., p. 4–5.

- Pierre Schaeffer cites first natural hearing (écouter), then the acoustic perception of sound (ouïr), third qualified listening (entendre), and fourth understanding and classifying the meaning of the sound (comprendre). Pierre Schaeffer, Treatise on Musical Objects: An Essay across Disciplines [1966], Oakland, 2017, p. 73–85. On the acousmatic field, p. 65–66.

In cooperation with

The exhibition is funded by

With kind support of

loop – raum für aktuelle Kunst, B-Part Raum Berlin, 2019